Looking for recently published academic sources on the history of every day people, every day lives, I stumbled upon two very different books. One focuses on ancient Mesopotamia and the era when cuneiform was the primary means of writing, the other on modern French people and purportedly the whole of human history. One is how a history book ought to be written, the other is confounding.

The one is Amanda H. Podany’s Weavers, Scribes, and Kings: A New History of the Ancient Near East.1 The other is Theodore Zeldin’s An Intimate History of Humanity.2 Dr. Podany is a workhorse of a scholar, professor emerita at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona who balances research and teaching well. Dr. Zeldin is a renowned French historian who is a fellow at Oxford and has earned many accolades.

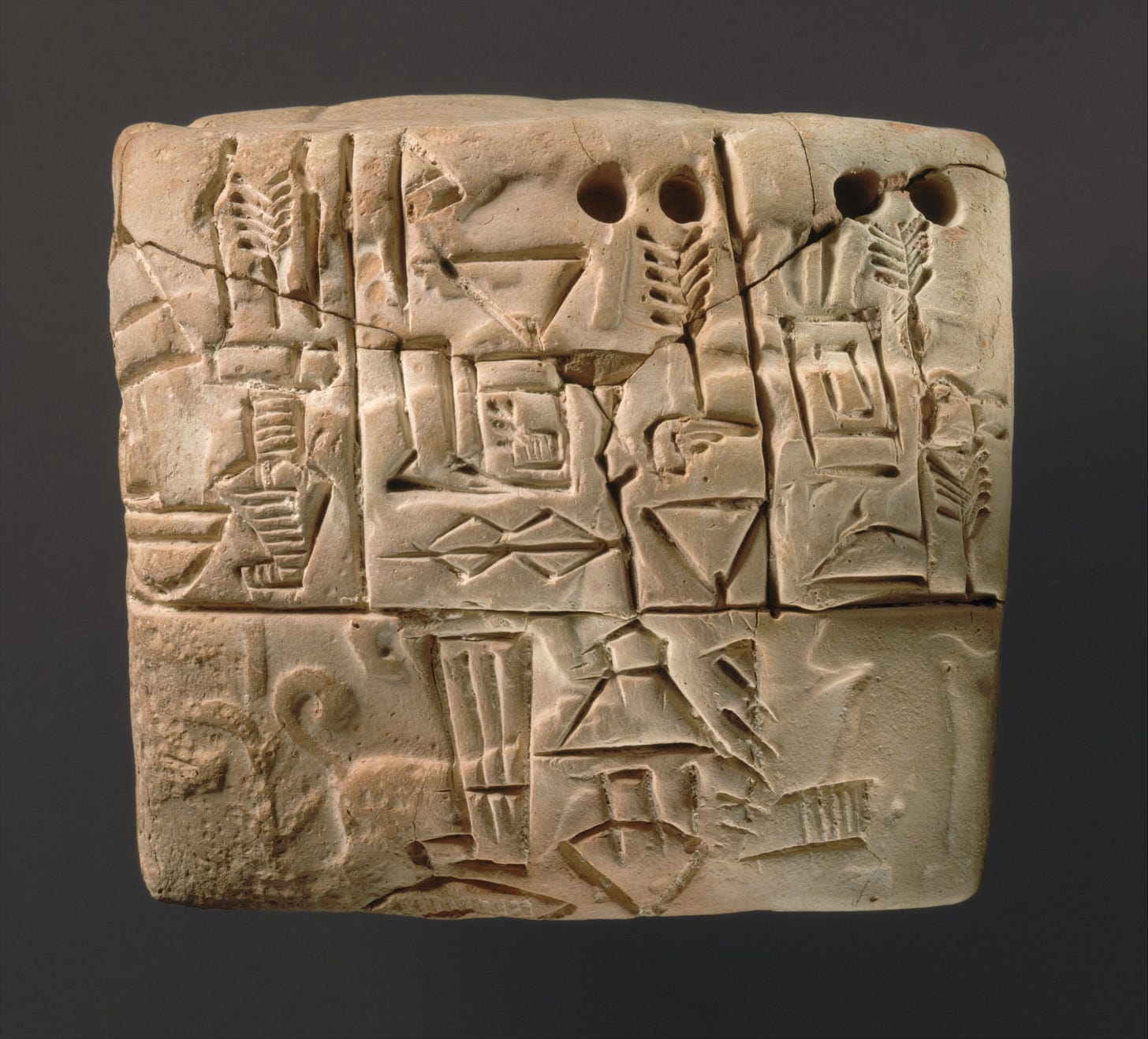

First the book that blew my socks off. Covering approximately 3,200 years of history (c. 3500-323 BCE), it provides its readers with real, concrete (literally3) insight into people’s lives under the succession of kings who gave political definition to eras and names to calendar years. While kings receive plenty of attention in the book, Podany’s focus on cuneiform—the script(s) that captured Sumerian, Akkadian, and then other languages, and, because clay tablets were used, records more of the cultures that used it more than from cultures that used papyrus or other media that don’t tend to turn into hard rock-like surfaces—brings alive the common or at least less-than-royal people. This framework is a real historical purpose for the book to fulfill, which it does, chapter after chapter.

A single sample from early in the book may suffice to get you to want to read the book. One of the first individuals named is Kushim, who lived and “worked in the Eanna complex [the temple to Inana] around 3000 BCE.”4 His job? To make sure the ingredients for producing beer (which did not include hops but did include herbs and/or date syrup) arrived at the temple and the deliveries of said produced beer were made. But he wasn’t the best at math. “He made quite a few mistakes in the totals that he recorded on his tablets,” which he signed.5 The math errors give Podany the opportunity to discuss schools, where cuneiform and math were taught. Students were given lists of professions to copy to learn cuneiform. The lists themselves become a gateway for discussing the slipperiness of terms in this time period.

These [professions] are listed in hierarchical order from the most important functionaries to the least. At the top, where you might have expected to find the en, the most powerful man in Uruk, is instead the nameshda, who seems to have been the top-ranked official. Curiously, the title of en doesn’t appear. Perhaps his exalted role was in a different category entirely from those of temple officers. It’s unclear, though; the term nameshda was later equated to the word for “king,” so it could already have been one of the en’s titles.

That’s just a taste of how “normal” people come alive in this book and inform our understanding of the historical context in which they lived, as best a historian can with the primary sources available. In the above block quote, please, also notice other excellent historical skills that Podany displays: precision and temperance in claims; an eye toward what makes the topic interesting to a wide audience; and an interpretation grounded in fact and primary sources. The result of these skills is a book of fascinating narrative that sheds new light on events familiar.

A fascinating narrative does not require bombastic claims. Caution may be the historian’s middle name. As Podany illustrates, “They would not have understood how we think, and it’s very difficult for us to understand them.”6 A perfect example comes a few pages later: “Obviously, the alleged reigns in the Sumerian King List were absurdly long and lay in the realm of legend, not history, but they tell us that the people of Early Dynastic Sumer probably believed themselves to be living at the endpoint of more than 400,000 years of civilization.”7 This is what historians mean when they say perspective is important.

Next the book that confounded me. Published thirty years ago, in 1994, An Intimate History captures modern angsts that have continued to today. Perhaps the angsts have even amplified with the internet, which, coincidentally began as a public institution around the same time the book was published. (I got my first email address as an undergrad and I was an undergrad in 1994.)

The modern angsts gave me such hope for this book. Every chapter starts with an ordinary and everyday sort of person, an individual you may get to know, by chance, at a grocery story or a coffee shop, if you’re the out-going type. This person has obviously shared with the author some very personal thoughts about their existence, so yes, their existential questions and thoughts. A theme seems to emerge from their thoughts, whether they know it or not, but the author, Zeldin, spots it and intends to use it to give the rest of the chapter shape. I have to say “intends” because the rest of the chapter crumbles like crumb cake. The rest of the chapter is supposed to give historical context to the emotion and/or angst the person exposed, “to show how they pay attention to - or ignore - the experience of previous, more distant generations, and how they are continuing the struggles of many other communities all over the world, whether active or instinct…among whom they have more soul-mates than they may realise.”8

The book began to provide me my own existential crisis, on repeat, starting anew with each chapter. The person is fascinating, the angst revealed is relatable, and I want to know more about the person, but the rest of the chapter is not coherent enough to offer a useable narrative to see the angst from a new perspective that will help dig me out of it. Some statements appear reasonable, but I later figured out that they did merely because I tended to agree with them. So, opinion is on offer in this book. Some statements made assertions the only discernible purpose of which was to transition from one odd historical reference to another. For example: “But conversation is not made just of questions: Socrates invented only half of conversation. Another rebellion was still needed, and it came with the Renaissance. This time it was a rebellion by women.”9 A leap from Socrates to Madame de Rambouillet is made by a “necessary” rebellion. (Can we really call upon historical artifacts to provide the rebellion that is “needed?” What kind of presumptions…? I feel another existential crisis coming on.)

I thought perhaps I was missing something about this book that was inhibiting me from drawing out its wisdom. So, I looked to book reviews for others’ insights. I found one by M. M. Mullaney, published in 1995 in Library Journal, which praised the book as “thought-provoking and immensely readable,” stating, “Zeldin attempts a history of human thoughts and feelings unfettered by considerations of historical epoch or culture.”10 That last bit — “unfettered by considerations of historical epoch or culture” — is how one could define the term “ahistorical.” Another book review captured my confoundedness with: “anyone informed about them [historical figures Zeldin references] is likely … to say ‘Well, yes, I suppose so’ and ‘Hang on a bit’.” That’s from R. Kaveney, whose review was published in 1994 in New Statesman & Society.11

By complete accident I happened to read these two books at the same time. It struck me that side-by-side they illustrate historians’ skills and fallacies, interpretation vs. opinion, tempered construction of the past vs. musings. This essay may be a musing, but if it’s sparked any thoughts about “doing history” for you, I’d love to hear them.

Amanda H. Podany. Weavers, Scribes, and Kings: A New History of the Ancient Near East. Oxford University Press, 2022.

Theodore Zeldin. An Intimate History of Humanity. HarperCollins Publishers, 1994.

The concrete reference is a bit of interesting trivia: in Uruk — you know, “one of the first cities,” that Uruk — the Stone Cone Temple had been constructed with a form of concrete made from cooked limestone, that is, with tons of limestone that had to be dragged (no decent wheeled carts yet!) from at least 50 kilometers away. The concrete made the structure waterproof and so naturally there was a pool in the temple. For unknown reasons, this temple was the last to be built with concrete, and mud brick became the dominant construction material afterward. (p. 22-26) So much for linear progress.

Podany, 48

Ibid., 50.

Ibid., 54.

Ibid., 75.

Zeldin, vii-viii.

Ibid., 35.

Marie Marmo Mullaney. Review of An Intimate History of Humanity. Library Journal, Vol. 120 (6) (1995): 112.

Roz Kaveney. Review of An Intimate History of Humanity. New Statesmen & Society, Vol. 7, Issue 326 (October 28, 1994): 49.

Jeanne, thanks for the Podany reference and review. These Sumerians are near to my heart. As for the other, I vowed long ago to avoid translations from French. And when I forget, the maddening digressions remind me. Claims for the sparkling clarity of French seem to be echoes of 18th century salons rather than lucid assessment in modern terms. It was a pleasure to read your careful evaluation from a historian-reader perspective.